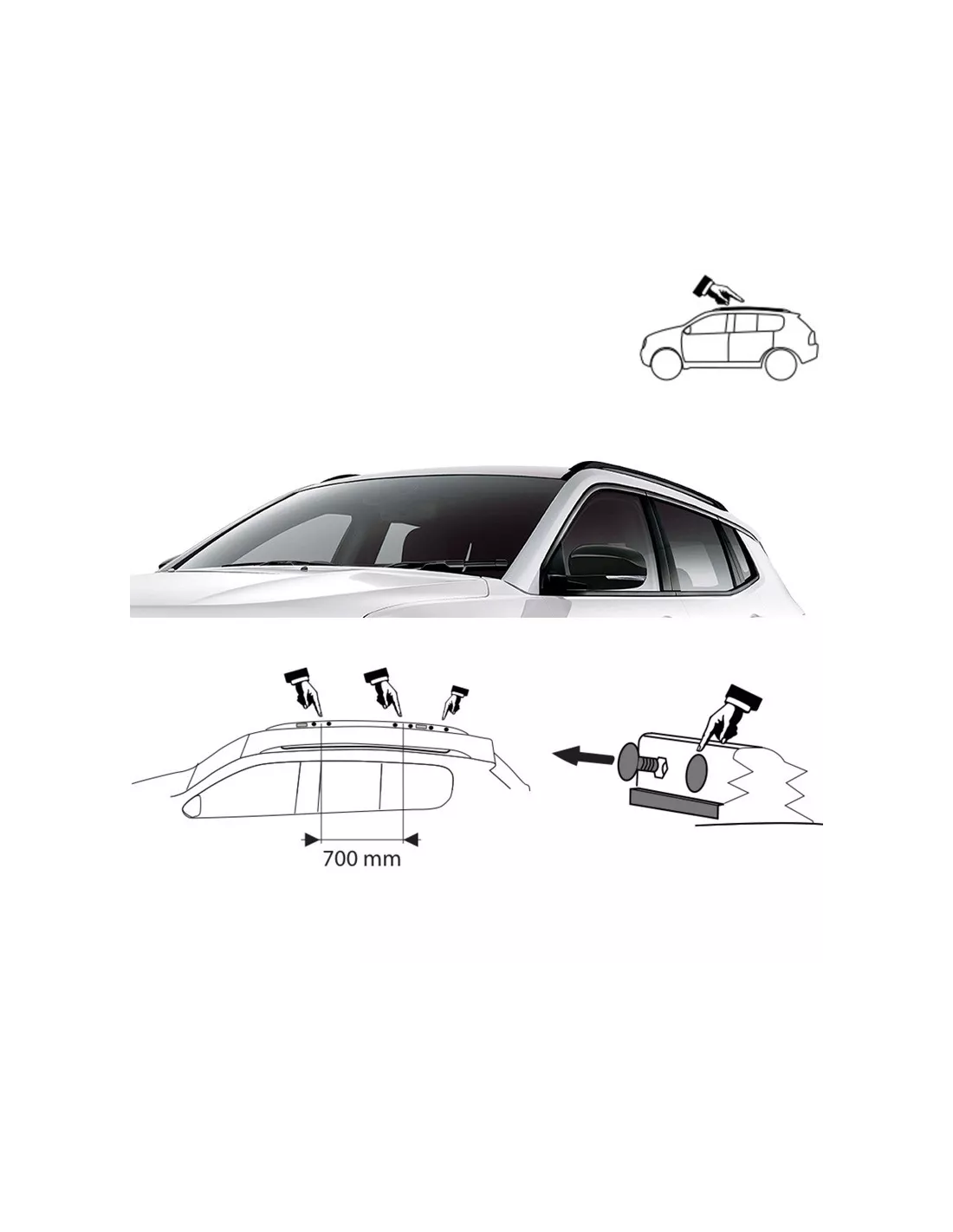

Barre Portapacchi Portatutto Per Jeep Compass 2017-2019, Auto Alluminio Bagagli Portabagagli Portabici Da Tetto Barre Trasversali Trasporto Longitudinali Accessori Per Viaggi : Amazon.it: Auto e Moto

Portatutto Thule completo di WingBar Evo e kit per Jeep Compass con profili integrati | Autoricambi Emmedue (Roma)

Barre Portapacchi Portatutto Per Jeep Compass 2011-2016, Auto Alluminio Bagagli Portabagagli Portabici Da Tetto Barre Trasversali Trasporto Longitudinali Accessori Per Viaggi : Amazon.it: Auto e Moto

2 Pezzi Auto Barre Portatutto Portapacchi per Jeep Compass 2017 2018 2019 2020,Barre Trasversali Portabagagli Portatutto Da Tetto Esterno Accessori. : Amazon.it: Auto e Moto