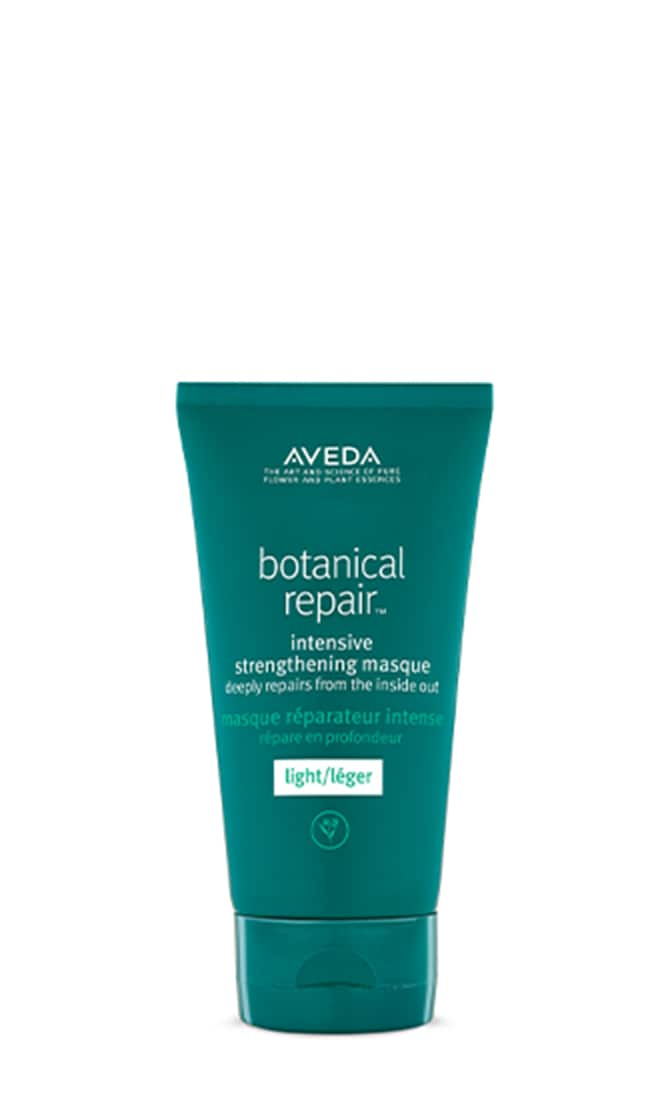

Spray Per Balsamo Senza Risciacquo Black Botanical Da 200 Ml, Spray Per Olio Essenziale Per La Cura Dei Capelli Per Tutti I Tipi Di Capelli - Temu Italy

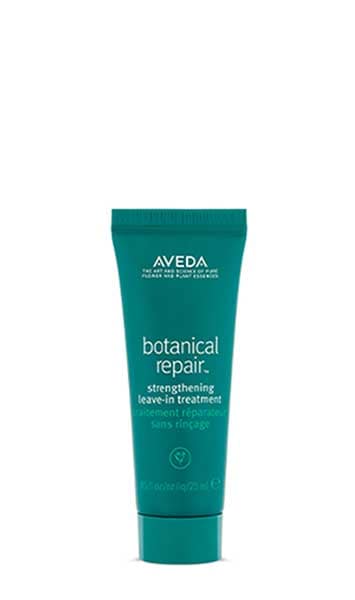

Amazon.com : Botanic Hearth Leave In Conditioner Spray - Hair Treatment Product Strengthens Dry, Damaged, Chemically Treated Hair - Adds Volume and Manageability - Leaves Hair Soft and Smooth - 8 fl