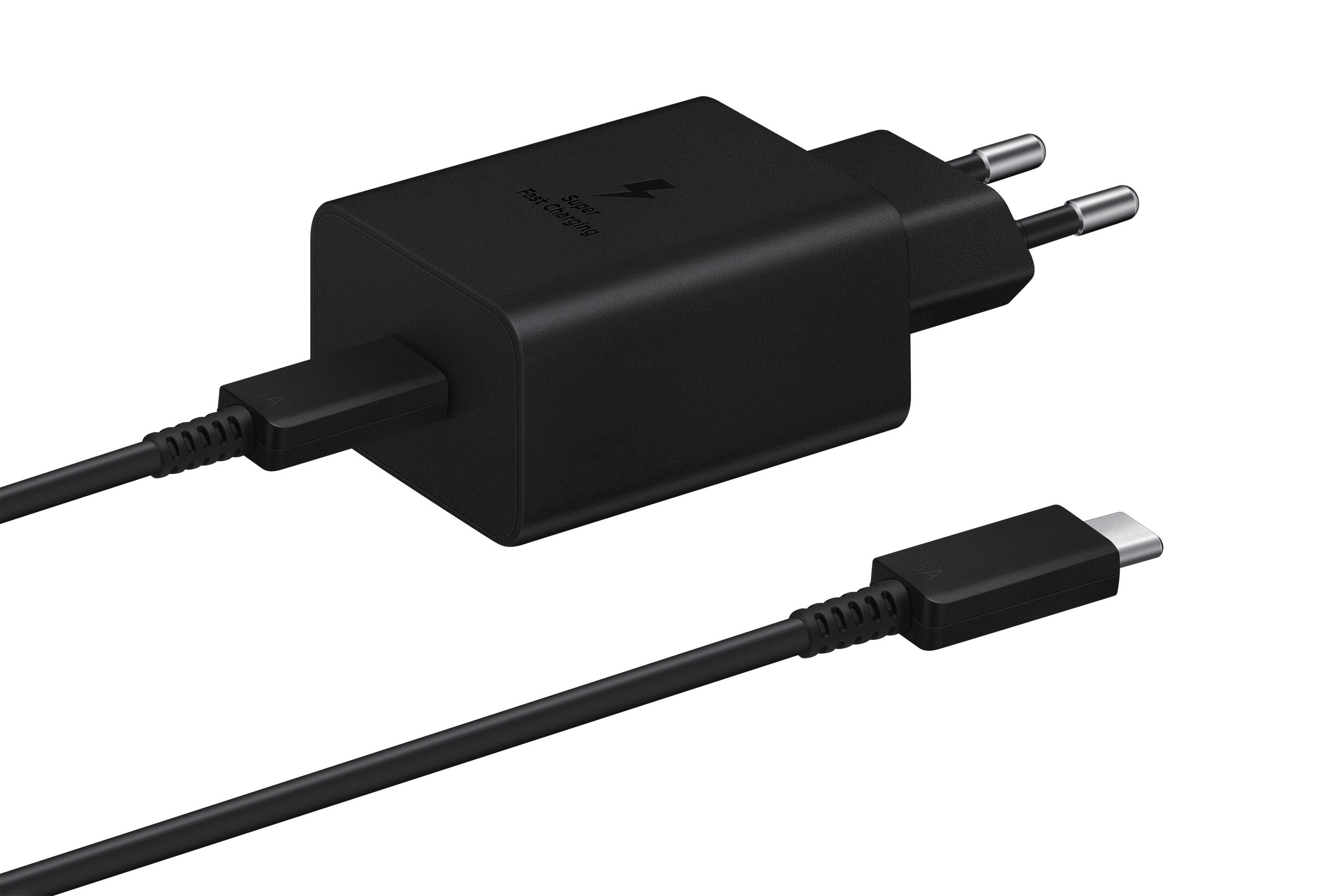

Caricabatterie Super Fast Charging (45W) con cavo da USB Type-C a Type-C | EP-T4510XBEGEU | Soluzioni professionali Samsung Italia

ZLONXUN Caricabatterie Caricatore veloce per Samsung Galaxy Tab A8/A7/A7 Lite/S6 Lite/S7 FE/S8, Xiaomi Pad 5 11",Huawei MatePad T10s, MediaPad M5 Lite, Lenovo tab M10 FHD Plus/P11/P11 Pro : Amazon.it: Informatica

Caricatore Rapido 45 W Caricabatterie Cavo Di Ricarica Da 2 M A 90 Gradi Di Tipo C Compatibile con Samsung Galaxy S20 Ultra S21 Ultra S22+ S22 Ultra 5G Galaxy Tab S7

Caricatore Ricarica Rapida 45W Doppio USB C, Super Fast Charging per Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra/S22+/S21 Ultra/S21+/ Tab S8 Ultra/Tab S7 FE/Z Flip 4/Z Fold 4, 20W Caricabatterie Rapido per iPhone : Amazon.it:

SAMSUNG Galaxy Tab S8 con caricatore – Tablet da 11" (8 GB RAM, 256 GB di stoccaggio, 5 G, Android 12) Argento - Versione spagnola : Amazon.it: Informatica

SAMSUNG Galaxy Tab S8 con caricatore - Tablet da 11" (8 GB RAM, 256 GB di archiviazione, 5 G, Android 12) Nero - Versione spagnola : Amazon.it: Informatica

CARICABATTERIE RAPIDO ORIGINALE Samsung Galaxy Tab S8 S8 Ultra S7 65 W USB C cavo di ricarica EUR 44,90 - PicClick IT

Ysevnotan Caricatore Originale 45 W USB C Caricabatterie Compatibile con Samsung S22+, S22 Ultra, S21 Puls, S21 Ultra, S20 Puls, S20 FE, Galaxy Tab S8, S8+, S8 Ultra, S7, PPS Carica Batterie -

Caricatore Samsung 45 W Caricatore Samsung Ricarica Rapida Caricatore Tipo C Ricarica Rapida. Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra/S23+/S23/S22 Ultra/S22+/S22 Note 20/10 Galaxy Tab S8/S7, con presa USB C Ricarica : Amazon.it: Elettronica

Per caricabatterie Samsung Pd 45w tipo C caricatore Samsung ricarica Super veloce 2.0 caricatore 25w Galaxy S23 S22 S21 + Tab S8 cavo USB C - AliExpress

Per caricabatterie Samsung Pd 45w tipo C caricatore Samsung ricarica Super veloce 2.0 caricatore 25w Galaxy S23 S22 S21 + Tab S8 cavo USB C - AliExpress