Olivia Garden - Fingerbrush Combo Small - Spazzola Piatta per Capelli Corti, Secchi e Districati - Testa Curva - Setole Cinghiale e Nylon per Lucentezza Naturale - Capelli Fini, Medi e Spessi - Nero : Amazon.it: Bellezza

Olivia Garden Ceramic + Ion Speed XL - Borsa con 5 spazzole per asciugacapelli extra lunga, 610 g : Amazon.it: Bellezza

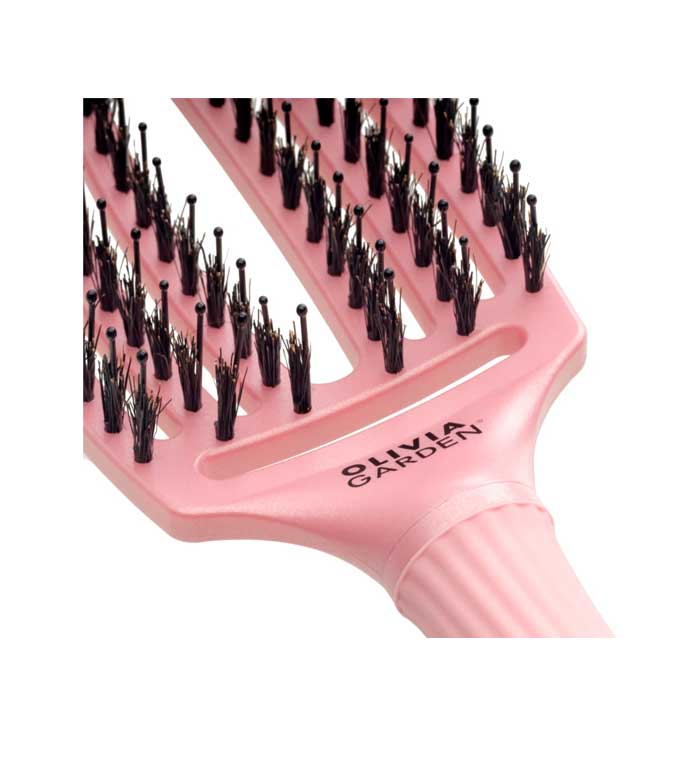

41998 OLIVIA GARDEN - ESPOSITORE 8 SPAZZOLE FINGER BLUSH - Morocutti - forniture per parrucchieri e centri estetici

41807 OLIVIA GARDEN - ESPOSITORE 22 SPAZZOLE CER+ION - Morocutti - forniture per parrucchieri e centri estetici

41828 OLIVIA GARDEN - ESPOSITORE 22 SPAZZOLE NANO THERMIC - Morocutti - forniture per parrucchieri e centri estetici