10 pezzi M10 tubo filettato femmina in metallo tubo a vite cromato entrambe le estremità con prolunga filettata interna per apparecchi di illuminazione - AliExpress

Tubo filettato in acciaio inossidabile 304, tubo metallico, tubo corrugato, tubo flessibile in acciaio inossidabile, tubo protettivo, lunghezza 1 metro,Diametro interno 25 mm, diametro esterno 29 mm : Amazon.it: Fai da te

Evotrade Viti di Congiunzione per Mobili e Maniglie ,Viti Metriche Tubo Filettato Dimensioni Scelta M6x30 F. | Leroy Merlin

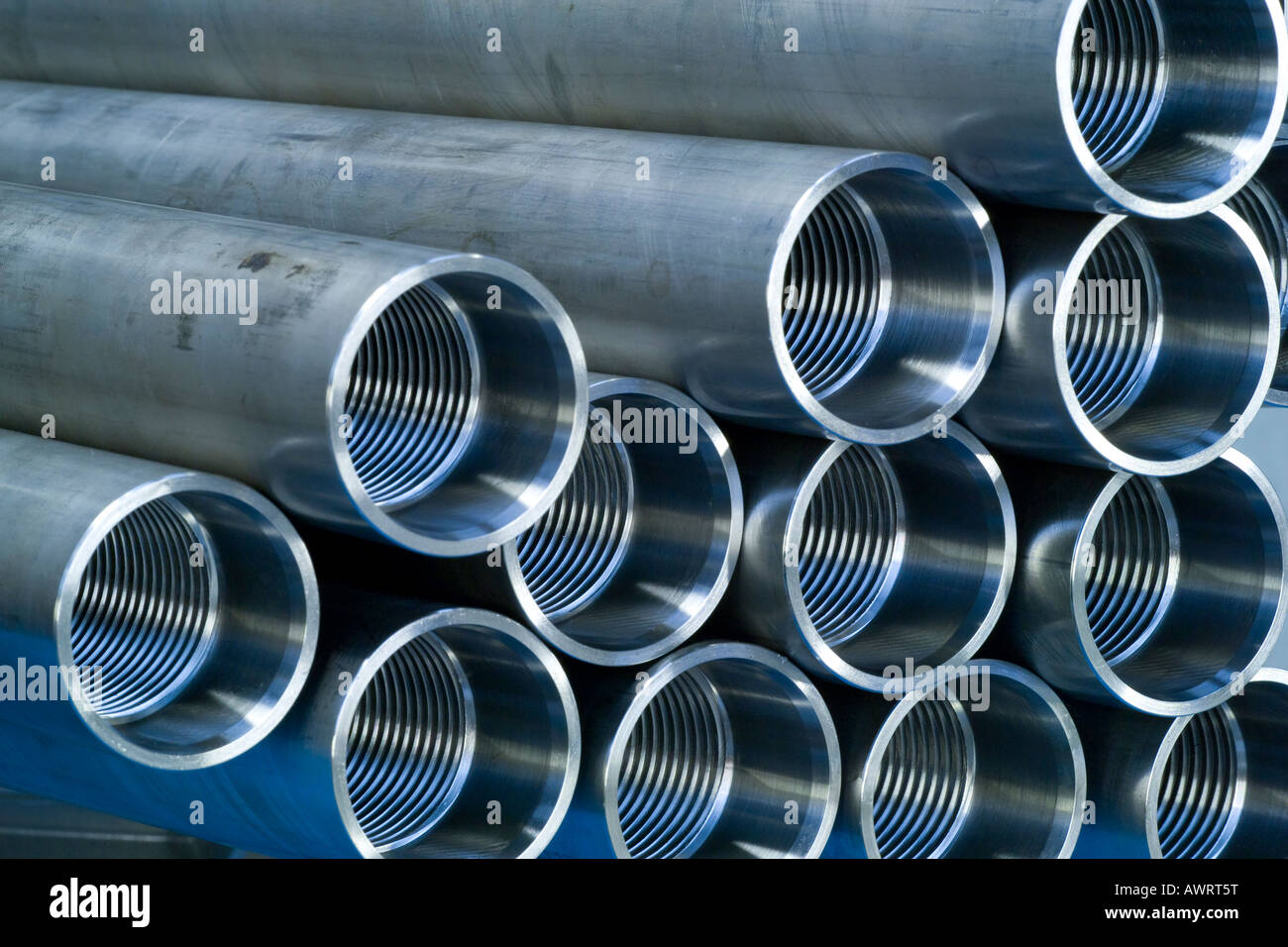

Giunto tubo filettato internamente con nipplo Ace in inox HF di ASOH (HF-7207) | MISUMI Online Shop - Scegliere, configurare, ordinare

TUBO,TIGE,TUBETTO,FILETTATO,50CM,500MM.LAMPADARI,UNIVERSALE,228/50,BARRA, FILETTATA,M10X1 . MONTARULI Service - Ricambi Elettrodomestici

DOJA Industrial | MANICOTTO FILETTATO M6 | PACK 10 | Manicotti filettati per Tubo idraulico Tubo acciaio | Tubo filettato per l'unione di sezioni di Raccordo rubinetto Idraulica tubi raccordi : Amazon.it: Fai da te

BSP 1/2 "3/4" 1 "Tubo di Raccordo In Acciaio Inox 304 MalexMale Filettato Tubo di Connettore 5/6/8/10/15/20/30 centimetri Asta Doccia - AliExpress

Tubo filettato ondulato, tubo metallico in acciaio inossidabile, coperture del cavo, tubo di protezione del cavo, lunghezza 1m, diametro interno (16mm) : Amazon.it: Commercio, Industria e Scienza