Tali Simboli Includono Fendinebbia Anteriore E Posteriore E Simbolo Automatico Del Faro - Immagini vettoriali stock e altre immagini di Airbag - iStock

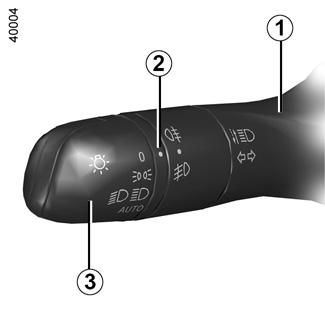

E-GUIDE.RENAULT.COM / Megane-4 / Prenditi cura del tuo veicolo (gruppi ottici) / ILLUMINAZIONI E SEGNALAZIONI ESTERNE

![Quiz Patente AB: Il simbolo rappresentato in figura si trova sul comando di accensione delle luci fendinebbia posteriori [FIGURA 717] | Quiz Patente! Quiz Patente AB: Il simbolo rappresentato in figura si trova sul comando di accensione delle luci fendinebbia posteriori [FIGURA 717] | Quiz Patente!](https://quizpatentelng.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/imgquiz/717.jpg)

Quiz Patente AB: Il simbolo rappresentato in figura si trova sul comando di accensione delle luci fendinebbia posteriori [FIGURA 717] | Quiz Patente!

Icona Dei Fendinebbia Posteriori - Immagini vettoriali stock e altre immagini di Attrezzatura per illuminazione - Attrezzatura per illuminazione, Automobile, Brillante - iStock

SHAARI Blocchi fari posteriori 2 Pezzi Fari Fendinebbia Posteriori Compatibile Con Cooper Per R56 R57 R58 R59 Funzione Come Fendinebbia Posteriore/luci Da Corsa/luci Posteriori (Color : Red) : Amazon.it: Auto e Moto

WUURAA Fendinebbia Posteriore 43 - Luce Di Arresto Della Luce Posteriore Indicatore Di Direzione Per Camion Ribaltabili Per Rimorchi Con Telaio : Amazon.it: Auto e Moto

2 pezzi fendinebbia posteriori rifila la copertura dello Styling dell'auto per Toyota Vitz Hatchback 2017

Nonuink Lente Fanale Posteriore Riflettore Per Auto Fendinebbia Posteriore Luce Freno Paraurti Posteriore Fendinebbia Per Toyota Per NOAH Per VOXY Serie 80 (Color : 4) : Amazon.it: Auto e Moto